"We tried to carry on as normal but my negative chatter started up again…

I'd never be one of those mums who could bake cakes for a school fare... or one of those mums who could rustle up costumes for the school play."

It is, perhaps, one of the facts of life that you are inevitably not going to get everything you want. But somehow, to not be able to conceive or carry a child to term for whatever reason, when you fervently desire for one, seems one of the cruellest tricks that life can play. Yes, there are those who are adamant they do not want children of their own, women and men, but the majority of people do wish to procreate and bring their own progeny into this world and seem to do so without any problems whatsoever, by and large.

To be denied that chance is to undoubtedly experience a sense of loss akin to losing someone who has been born and lived a life, however long or brief. Though it is also a very different loss, perhaps absence might be a more appropriate term, because you will never quite be sure what it is, who it is, that is missing from your life. You can imagine, you can dream, you can wonder, but you can never truly know.

Consequently, like BILLY, ME & YOU (about the loss of a child) by Nicola Streeten and HOLE IN THE HEART (having a child with Down's Syndrome) by Henny Beaumont, both also published by Myriad, this is one of those works that leaves you feeling rather raw emotionally. Which is clearly how Paula felt upon finally accepting that her dream of having a child was gone, which in her case as she explains, was at least in no small part due to her ongoing battle with ME. I don't doubt there are elements of that pain which are still with her today, and probably always will be. How can that not be the case? But Paula has at least been able to come to terms with it, begrudgingly perhaps, to some degree, and find a measure of peace.

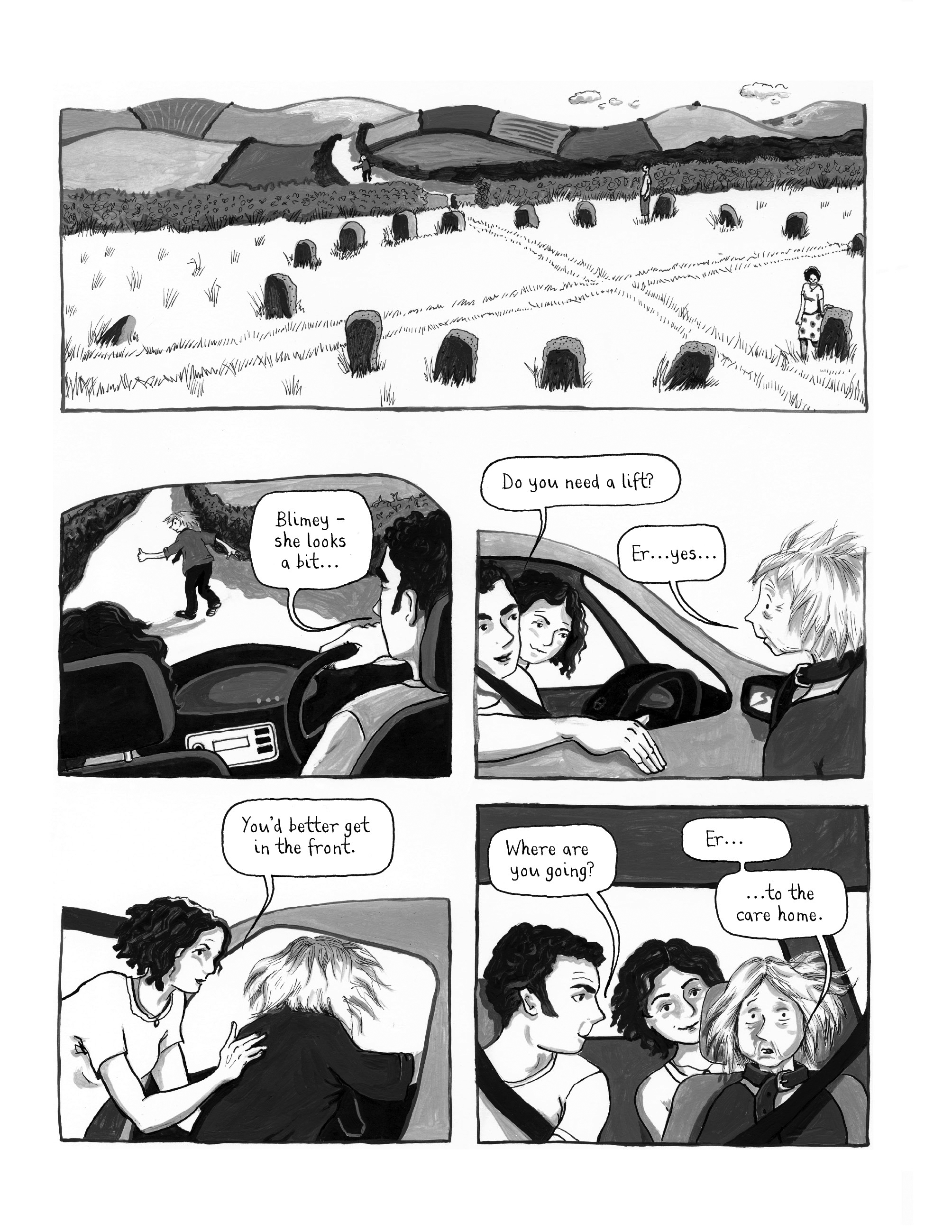

This is her story, of how a little girl growing up in the north east together with her best friend, ended up travelling a divergent path entirely due to the vagaries of fate. Upon reaching adulthood her friend quickly settled down and became a mother with seemingly effortless ease, having a beautiful daughter and embracing being a parent in all its innumerate, relentless ups and downs. Whereas for Paula, who would have welcomed the maelstrom of madness that motherhood brings with open arms, well, matters were sadly much more complicated and rather less fulfilling.

I will have to hold my hand up at this point and say this is a book which it is probably impossible to digest with an entirely objective perspective. Whether you just don't want kids, or desperately do but just haven't met the right person yet and time is ticking, are currently trying but are struggling to conceive or carry a child, currently have a child or children, were sadly unable to, or indeed are currently pregnant, you have a subjective world view on this issue. It is inevitable. But given this is a work about trying to allow people to see a traumatic situation from another's perspective, I don't think it remotely matters. In that sense this is a very interesting work in that it will engender entirely different feelings in the people that read it.

I would imagine those who wanted children and were unable to do so will have the closest sense of what Paula has been through rekindled rather painfully. Those, like my wife and I, who ended up going down the route of IVF to get our daughter, will be reminded once more just how fortunate we personally were to overcome our fertility issues and know just what Paula has missed out on. People struggling with fertility currently will definitely empathise with the agonising uncertainty and not-knowing Paula and her chap went through, combined with wondering just how it will ultimately turn out for them. People who just popped kids out without any problems may well feel sorry, but really can't hope to grasp what they have endured, despite what they might think. And there may well be some, not wanting children themselves, who probably think they've simply swerved a bullet.

The point is, this is her, their, story and Paula does an incredible job of allowing us to understand just what they went through, indeed, what they are going through. And actually, on that last point, as someone who does suffer with ME, Paula does ponder deeply upon whether having children would have been a real uphill struggle for her. I gained a slight sense, rightly or wrongly, of looking for crumbs of consolation where truly there were none for her, but it's just part of the indefatigable honesty Paula pours into this work, when bone-sapping fatigue was in fact at times her mortal enemy on several levels.

What this work also does, in addition, is allow Paula to look at society's perceptions of women, particularly in relation to children, and how they have and haven't changed since her childhood. In that respect, like Una's BECOMING UNBECOMING about her childhood during the Yorkshire Ripper years and sexual violence towards women, there is a dual narrative going on which neatly broadens out the conversation.

Artistically, I was extremely impressed. I've only seen a few mini-comics and short strips that Paula has done before, but this is very accomplished work. The linework combines real fluidity and motion with a gentle neatness that enhances the detail. Neither under-inked nor over-inked, just a perfect weight, it gives a robust purpose to the art that is also very easy on the eye. A real talent and this was a very deeply moving read as I am sure it will be for most people.

And I should add, despite the upsetting subject matter, there are happier times shown too, which do underpin the whole story, told by a clearly very strong woman, despite her recurring physical frailties due to ME. I have only had the pleasure of meeting Paula once, but she made me smile by reminding me in occasional depictions of her here, of an impish mischievousness I definitely detected in person!

A veritable triumph of autobiographical comics, which will only help to further much needed conversation on a very difficult, harrowing subject for many people, whom we should all have boundless empathy for, whether we truly understand their suffering or not.