“There was a time when you couldn’t eat a meal with any decency without the potters from Stoke... Can’t grow a bloody teapot for toffee any more. Four thousand kilns gone later and it’s gone that dark over Bill’s mother’s you realise just how much daylight those kilns let in.”

(‘Pot Luck’)

The Staffordshire Potteries famously form the thematic bedrock of a series of novels by the great social novelist Arnold Bennett – Anna of the Five Towns, The Old Wives’ Tale, Clayhanger – whose work rigorously exposes the harsh working conditions in the ceramics industry at the height of the Industrial Revolution. A century later, the despoiled Midlands of the immediate post-Thatcher era is mapped with uncanny and devastating acuity in the work of the sadly deceased weird fiction writer Joel Lane, whilst the ambiguous, denatured land of shopping precincts and ‘new business opportunities’ is the subject of novels by Catherine O’Flynn and Kerry Hadley-Price. With a long-overdue resurgence of interest in regional writing, the stories and novels of Lisa Blower, which centre the lives and histories of the people left behind in the wake of successive government austerities, should be of paramount importance in putting the literature of the West Midlands on the map.

I first came across Lisa Blower when I was asked to review a book of short stories on the science of sleep (Spindles, Comma Press 2016). In what turned out to be a fascinatingly original anthology, Blower’s story ‘Trees in the Wood’, in which two grieving women come to make sense of their lives through the lens of the other, was a highlight for me. In this new collection of stories spanning nine years of published writing, Blower fulfils this first promise and then surpasses it. It’s Gone Dark Over Bill’s Mother’s is – in my own words from that earlier review – emotionally draining, hard-hitting and brilliantly written.

The overarching theme uniting this collection is family. In the collection’s lead story, ‘Barmouth’, which was shortlisted for the BBC Short Story Prize in 2013, an annual holiday in North Wales is the repeating motif in a narrative spanning several decades of one family’s history.

“It’s 1982, around five o’clock. We’re at war with Argentina... I see all the things that haven’t changed and cheer at each one. The black spindle towers of the railway bridge, the flags at the top of the helter skelter, the neon lights of the prize bingo, the Shell Shop where I’d buy gifts for schoolfriends, the Smuggler’s Rest where I’d be allowed scampi, adult portion, and cheesecake.”

The narrator’s enthusiasm for the holiday is gradually eroded as the years bring their changes: the narrator grows from being a hopeful, imaginative child into a troubled young woman who is forced to give up her own child for adoption. Her father is made redundant, then her parents divorce. Grandpa dies, Mother develops Alzheimer’s, the narrator’s sister escapes her difficult background to become an artist. The story works itself out through repeated patterns of language that are both painful and comforting, reflecting how family is simultaneously nurturing and an entrapment. The adult members of the narrator’s family are discontented people who lack the capacity to properly articulate their discontent. ‘I’m tired of just making do,’ says the mother at one point. ‘This isn’t about Barmouth.’ Such patterns and cadences of family strife are so familiar they are painful to read, though by the time the story closes the narrator has achieved a measure of stability.

In ‘Drive [in seventeen meanings]’ we find ourselves in the company of a mixed race teenage boy named Juke. As the story opens, Juke’s Thai mother is driving frenziedly towards the home of her sister. Slumped beside her in the passenger seat is Juke’s father, unconscious and bleeding from a stab wound. Life in England has not turned out the way Juke’s mother dreamed it would: the professional man she married has quit his university job to open a car wash, Juke is out of control and coming increasingly under the influence of a gang kid called Moth.

The story is structured in seventeen truncated episodes. Like scenes from a film, they intercut the narrative’s forward progression with the background leading up to it, though it is fury that is the real driving force of this story. Juke is in thrall to Moth but he fears him, too. He is desperate for help, and his mother’s seeming indifference to his situation incenses him. His mother is so deeply immersed in her own misery she is driving in circles. Her emotional appeal to Juke at the end of the story may yet offer a way of moving forward, for both of them.

Told in the second person singular, a technique that clearly reflects the inspiration Blower has drawn from Alan Bennett’s popular series of one-hander teleplays from the 1990s, Talking Heads, ‘The Land of Make Believe’ tells the story of a young woman, Dee, who finds herself pulling away from her family background and entering a no-man’s-land in which she fears she will never be properly accepted or understood. Dee’s mother is a sex worker and the single parent of four children. Indulgent of her eldest daughter’s passion for the pop group Buck’s Fizz, she encourages her to achieve her potential whilst warning her against forgetting where she comes from. ‘You’re too clever for your own good,’ Dee’s mother warns her, ‘and you’re wasting it already, because Cheryl Baker isn’t even Cheryl Baker. Her real name’s Rita Crudgington and don’t ever forget who you are.’

Dee’s classmates at the local grammar school seem determined to ensure that forgetting isn’t an option. ‘Your mum’s a slag,’ they tell her, ‘and shit breeds shit and scum like you from down the Abbey have no place being at a school like this’. Dee’s life as a student is marked by pent-up anger and a sense of alienation – she is not like other students, yet when stood against the backcloth of her own background she will always stand out:

The most formally ambitious of the family stories, ‘The Land of Make Believe’ is a moving and uncompromising narrative about class divisions and the pain of moving on, about the impossibility of escape and getting through anyway. This is a story of coming to terms with the sense of betrayal that often accompanies self-discovery, a story that reminds us that what most unites Blower’s family narratives is their sense of compassion.

‘Broken Crockery’ won the Guardian National Short Story Award in 2009, the year an ageing Margaret Thatcher was reported to have broken her arm in a fall at her home. The story is told by a young girl whose beloved Nan has just been taken into hospital. She conceals her anxiety about her sick grandmother within a fantasy about Nan and Margaret Thatcher being in hospital together. She is in no doubt her grandmother would have plenty to say to Mrs T:

“It’s not very nice to do well at making people cry. Those people are called bullies... Maybe my Nan is bullying Margaret Thatcher and drinking all her Lucozade. Maybe Margaret Thatcher is still bullying my Nan even though she knows my Nan’s bones are broken. I hope my Nan has better pillows and more Get Well cards. I don’t want my Nan to be best friends with Margaret Thatcher. That would be weird. Margaret Thatcher would say our house was too small and needed a good bottom clean. She might even send my mum to war.”

‘Broken Crockery’ is a beautifully poignant tragic-comedy, bursting with pathos and heart, cleverly dependent on the reader not only intuiting but remembering more than the child narrator understands. In this story, we are Nan, looking back at the Thatcher years, still not able to properly process the damage that has been inflicted. In the background, the young girl’s weeping mother must soon tell her daughter the news that will change her world forever.

In lives that have been shaped by such shattering blows, the trauma that recurs most often through these stories is the stress of redundancy. In ‘Pot Luck’, Mrs Johnson prepares food in her home for those who can’t afford a square meal in return for small donations. In words made brittle through anger, she charts the decline of living standards for ordinary people since the closing of the kilns. ‘I had a big life once,’ she insists. ‘But then his big job went, ping went the big dreams, and the big house got sold at a bargain bin rate... I remember standing in the shop, shortly after he left, seven pence short of a split bag of rice. Seven pence short of a split bag of rice. That’s when you start to think you’d rather die than ask the big queue behind you for a bit of small change.’

The end of the story sees Mrs Johnson addressing the reader directly, asking for help. In ‘Chuck and Di’, a less famous Di Windsor describes how the royal wedding turned out to be a boom time for the potters of Stoke, how her husband Charles, who works as a gilder, subsequently has a breakdown when he loses his job. Chuck sets up a business using his pension money, buying and selling commemorative china. As it turns out, Chuck’s business is more about buying than selling, and Di is finally at the end of her tether.

In these stories and more, Blower delivers a scathing indictment on the monetary policies of the 1980s, the mass redundancies that inevitably followed in their wake. As characters reflect on how having a job is about more than just money, these stories show again and again how family ties are eroded and communities destroyed. Blower is also not afraid to explore the more recent tensions that have arisen through the arrival of asylum seekers in already depleted communities. In the harrowing story ‘Hoops’, alcoholic teenager Rae is under threat of having her newborn daughter placed in care by social services. Rae’s boyfriend is Mo, an Egyptian asylum seeker consumed with guilt at having escaped the conflict in his homeland. Rae’s traumatised and racist Uncle Chalky is in hiding, a deserter from the British army in Iraq. The hopelessness of the situation for Rae’s mother Jean and sister Lo still does not prevent them from wanting to protect their loved ones.

In ‘Abdul’, longlisted for the Sunday Times Short Story Award in 2018, a social worker collects an Afghan asylum seeker from a holding facility in Kent to drive him to his allocated YMCA accommodation. Abdul believes he’ll be taken to Birmingham and expresses anger and frustration when he realises he is bound for Stoke instead. This story conveys a searing glimpse of the incalculable gap between the life this young man expected and what actually lies in wait for him, the equally unbridgeable gulf between the well-meaning narrator and her desperate charge.

In her acknowledgements for this collection, Blower mentions a ‘novel that didn’t make it’, but that nonetheless became the basis for several of these stories. I cannot help wondering if ‘Featherbed Lane’ – my personal favourite – is one of them. This story reads like part of a crime novel. Frances has returned to her home town after an absence of twenty-six years. She runs into an old classmate, Breda, in the supermarket, and soon discovers that Breda is now living in Frances’s childhood home on Featherbed Lane. We learn how Breda had a breakdown after her best friend was murdered, how she is convinced that Frances has been concealing the truth about what happened. There is more to the story, however, and when Frances gets talked into visiting Breda in her old home, she discovers that Breda’s obsession with the past is a cover for darker secrets of her own.

Blower makes superb and deliberate use of repetition in this story. Words, phrases and whole sequences of sentences appear again and again in an effect that mimics the recursive nature of memory, circling backwards in an attempt to recapture what is real, the stuck-record nature of imperfect recall. ‘Featherbed Lane’ unfolds as a series of flashbacks, or flash-photographs, and though the story works well as it stands, I did find myself hoping that Blower might one day consider returning to these characters and drawing out their histories at greater length.

Though the dominant mode of this collection is impassioned social realism, Blower reveals herself everywhere as a highly versatile writer, delighting in formal experimentation and linguistic inventiveness. ‘Fron’ is a ghost story, ‘Happenstance’ is told entirely through dialogue, ‘Prawn Cocktail’ is a deliciously wry little story about how to write a story. Most of all, Blower is finely attuned to the resonance of place and the music of speech. I came away from this collection with the sense that here is a writer who could take her talent in any direction she wishes.

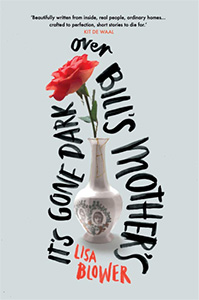

It’s Gone Dark Over Bill’s Mother’s by Lisa Blower is published by Myriad Editions